One would have to know more about my mind and my habits to understand my complex connection to Black History Month.

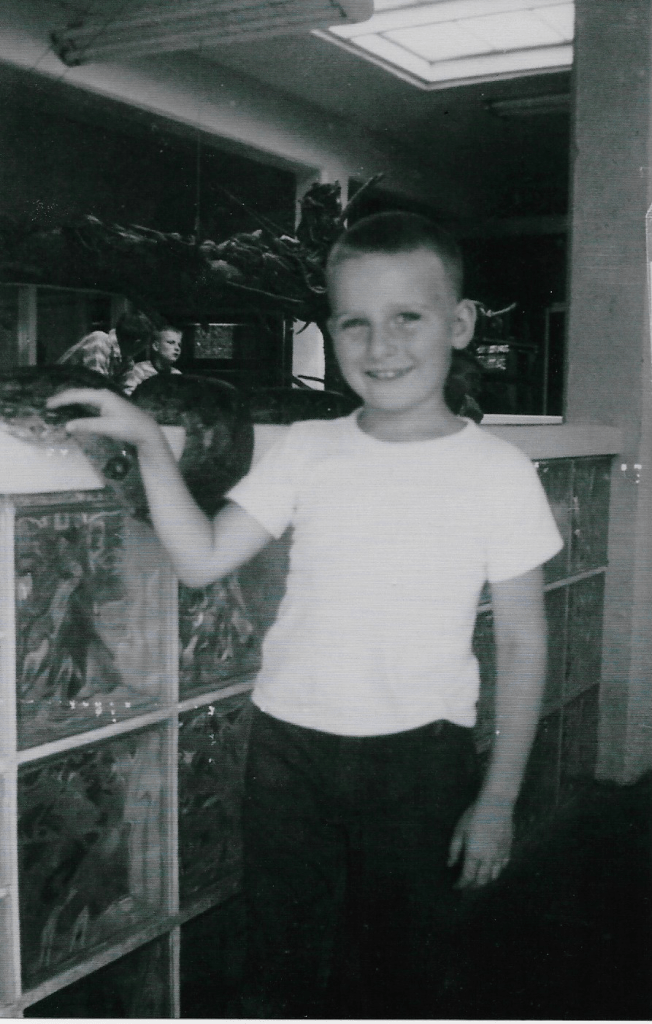

First, my mind. Among my most vivid early school memories comes one from kindergarten. Although one day on the way home from school I was hit by a car, my clearest recollection from that year at Kagel (seriously) Elementary School was not about being slammed in the crosswalk. No, the sharpest memory was the task of finding what’s missing from a picture: the chair with three legs or the clock with one hand. We 5- and 6-year-olds did one or more days of in-class testing, rotating through small groups. I suspect educators were looking for developmental delays and learning difficulties. I recall doing well on some of the early challenges, but as the illustrations increased in number and complexity, I missed some. For me, a shirt with no buttons was an obvious problem. But a fence missing a picket or two? In my family, these would not be so much problems as realities. We would be resigned to some things out of our control.

In my nearly seven decades since kindergarten, I have noticed repeatedly my reliance on visual cues and the associated comfort and confidence these bring me. In my work, I rely on evidence-based models of behavior change, factors associated with successful implementation of programs, and organizational infrastructure that allows for the greatest access to services with wide-spread acceptance. I carry these models in my head in the form of circles, pyramids, and steps. In other words, I’ve been using my kindergarten challenge of noticing what’s missing to foster memory and provide resources to others.

My mind also feels calmed by some sense of order, but not in an obsessive way. When I set a table, I am less concerned about the etiquette rules about silverware placement than I am about things looking attractive and cared for. If I am alone, I still take a moment to be pleased about the care I am taking for myself. Again, I have a picture in my mind of what looks pleasing and thoughtful, and I work to provide that to others. This attention to visual detail has at times been the source of ridicule by some who find it fey or precious. At other times, this talent is sought out when my approval is wanted for an aesthetic decision.

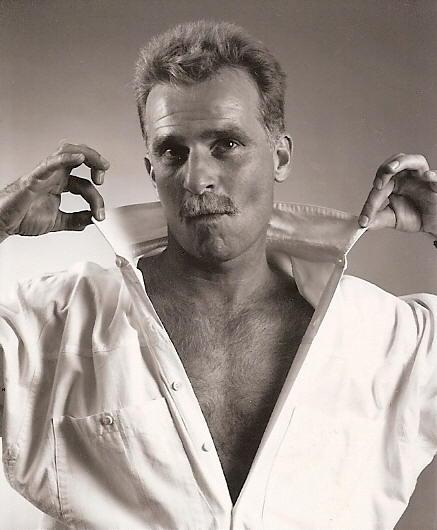

My habits are next. My clothes are on hangers; my sweaters, folded. Shoes I wear often sit in pairs on the floor. Those I wear infrequently are in labeled boxes on shelves. I use coasters under glasses. Pens are in a cup on my desk. Shades are open to the same height. Lights are generally off when I am not in a room. The lint trap in the dryer is cleaned when I remove my clothes from it. My spices – and there are many – are alphabetized. Though I do so much less during this pandemic, I have enjoyed for years putting out my clothes for the next day the night before.

These habits may look like close cousins to some of the ways my mind works. I guess they are. They may to many seem particularly middle class, and I guess they are that, too. But their origins, like that important kindergarten lesson about what is missing from the picture, are about not looking poor and not seeming foreign or different or other. As a raised-poor, raised-Catholic, Jewish boy of first- and second-generation American parents, fitting in was critical. At the time, my Jewish family was sometimes seen as people of color. As were our Irish Traveler family. And our Sicilians. My mother’s mantra was that we were poor, but not dirt poor. Color was scrubbed off us physically and metaphorically.

As I grew up in what is still Milwaukee’s most racially and ethnically diverse neighborhood, our differences were not so much talked about as felt. We didn’t talk about our Mexican neighbors. At all. Nor about the Roma guy who sharpened knives, the Italians with the horse drawn wagon that brought fruits and vegetables once a week. Or the Black men who delivered coal in big leather sacks on their shoulders. To talk about the differences would have required that we feel the steel wall between us and the Protestants on the other end of the block or the glares that kept us out of shops that were too up scale for us.

But, back then, all the adults across the various ethnic divides, regardless of their differences, could complain about prices, landlords, bosses, know-it-alls. They could be suspicious of education – both too little and too much.

At 7 or 8, I was one of a handful of white boys at the Franklin Street Boys’ Club. The Black boys were more gregarious, connected, athletic, and all around skilled. Weekdays at Catholic school were white. Saturdays at the Club were Black. I took three busses to get to the club on my own. I remember needing those boys, and them not needing me. Around this same time, I recited the Gettysburg Address by memory to my all-white cub scout troop. I recall crying afterwards because of the beauty of the language and its contrast to the inequities I was starting to see.

My family was quite late to the television era. Later still to the family car. But, while Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Dale Evans, and Howdy Doody were regular fair, I recall best seeing Mahalia Jackson, Pearl Bailey, and Lena Horn. There were also Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole, and Sammy Davis, Jr. I recall, too, our first family car trip – a vacation to Mount Rushmore, a drive through Native lands to see presidents hewn into sacred rocks. My deepest feelings about that trip are associated with never stepping off tarmac, even once, with unanswered questions about Native resistance, and with a rear wheel falling off our jalopy at the base of the mountain.

When I was recently asked to recall times that I have witnessed racism, I felt oddly numb. On one hand, I could recall dozens of early memories of seeing, hearing, observing racism. But witnessing it? As in, “Can I get a witness?” I would now describe the observation of racism by my family as adjacent: noticed, next to, disquieting but not disruptive. The absence of Black people deeply connected in my family’s life – even the general absence of Black people in American history – would be like those missing pickets in a fence, not so much a problem as a reality. To notice Black history, we would have needed to get more honest about our own history. We’d have to acknowledge our Irish Traveler history, our Jewish history, our Russian and Sicilian histories. We’d need to acknowledge our working poor conditions for what they were and recognize that no amount of order would make them less onerous. Further, there is nowhere that genocide, enslavement, and persistent subjugation fit in our annual patriotic visits to a cemetery on Decoration Day or to parks on Independence Day.

So, this is a bit about what makes Black History Month complex for me. My ignorance is born in absence, resignation, and fear.

What makes it simple, however, are the daily makings of history that I now witness: Margo, Ricardo, Ericka, Gatlin, Brenda, Noland, David, Denise, Rudy, Rodney, Norma, Roderick, Brigitte, Damia, Liddie, Kai, Rivera, Gregory, Jamaal, June, Warren, Kofi, Shahanna, David, Raven, Dennis, Paula, Sandra, Shawnika, William, Mandella, Everett, Barbara, Ronnie, Carmen, Nicola, Josh, James, Teyanna, Shon, Lorenzo, Michael, Michelle, Melissa, Bailey, Mischelle, Debra, Jaquilla, Sumaiyah, Syd, Ciera, Danny, Adam, Ava, Cleo, Stefani, Tatiayana, Louis, Leslie, Sheila, Andre, Bobby, Marquita, Ray, Susan, Robert, Scott, Theo, Samantha, Demetrius, Joseph, Chris, Barbara, Kim, Linda, Tiffany, Amy, Karole, Dre, Alonzo, Kellye, Warren, David, Quincy, Linda, Nick, Zandra, Gerald, Erin, LG, Isioma, Daniele…

You have touched so many chords in my life’s journey – and yes, complexity is definitely what I feel as well. In addition, sadness about my lack of awareness for so long.

LikeLike